Ken Saro-Wiwa’s legacy lives on: Nigeria’s Niger Delta still battles oil pollution 30 years after his death

Three decades after Ken Saro-Wiwa’s execution, the Niger Delta remains scarred by oil spills and broken promises, as activists say the late environmentalist’s warning against Nigeria’s oil dependence has never been more urgent.

Ken Saro-Wiwa was the man who forced the world to confront the devastating impact of oil extraction in Nigeria’s Niger Delta. He shattered the illusion that oil wealth would bring prosperity to the country.

"If we had a proper system, they would find that there is not so much oil money around anyway," Saro-Wiwa told DW in November 1993.

"Oil is causing a lot of devastation, which the country has not paid for and which it will pay for in due course. So people should go and look for other sources of sustenance instead of eyeing oil," he said.

Just days later, military ruler Sani Abacha seized power and established a brutal dictatorship. Two years on, Saro-Wiwa and eight fellow activists — later known as the “Ogoni 9” — were executed.

Supporters insist the activists were murdered by a corrupt system determined to protect profits from oil. Yet Saro-Wiwa’s legacy endures.

'Courageous man'

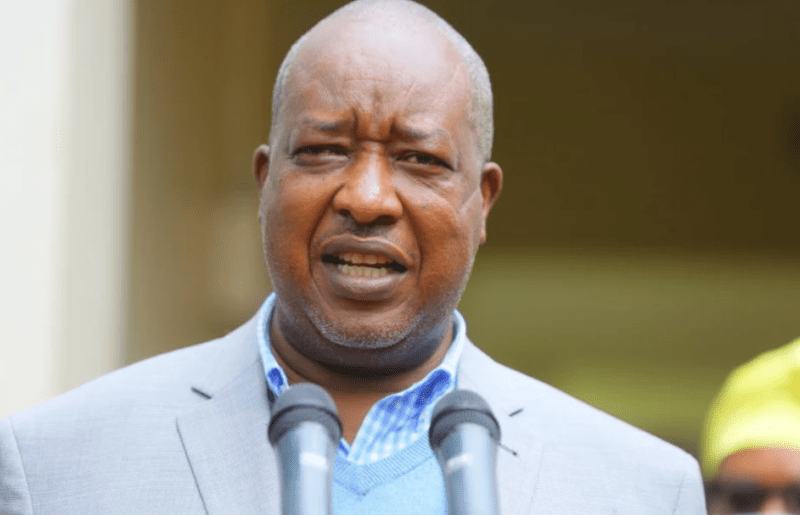

Nnimmo Bassey, now one of the Niger Delta’s most prominent environmental activists, describes him as a "courageous man" and a "visionary."

"He was very much ahead of his time," Bassey told DW.

Oil was first discovered in the Niger Delta in the 1950s by Shell, then a Dutch company. That discovery unleashed decades of unchecked environmental destruction, despite fierce opposition from the Ogoni people. Water became undrinkable, and vast farmlands were rendered useless. Years of protest by Ogoni leaders failed to bring change.

Resistance was revived when Saro-Wiwa — already a respected author and playwright — founded the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP) in 1990. The group accused Shell of destroying the local environment and excluding residents from the benefits of oil production.

MOSOP quickly drew global attention. In 1994, Saro-Wiwa and the organisation received the prestigious Right Livelihood Award.

Environmental genocide

Bassey, himself an author and Right Livelihood laureate, says Saro-Wiwa spoke truth without fear.

"People like to be more politically correct. But he just called what was going on: an environmental genocide against the Ogoni people."

In 2011, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) released its first scientific study of the region, confirming that oil production had caused an ecological disaster in Ogoniland.

The Bodo River in the Niger Delta is so heavily polluted that using the water for drinking and fishing is banned. (Photo: Yasuyoshi Chiba/AFP/Getty Images)

The Bodo River in the Niger Delta is so heavily polluted that using the water for drinking and fishing is banned. (Photo: Yasuyoshi Chiba/AFP/Getty Images)

Saro-Wiwa’s movement also disrupted oil operations. In early 1993, MOSOP organised a peaceful protest involving nearly 300,000 Ogoni in Rivers State. Shell soon withdrew most of its staff for safety reasons and drastically reduced production.

Later that year, Saro-Wiwa told DW: "When the federal government takes away 97 per cent of the oil money, but does not take away 97 per cent of the pollution, it is doing something wrong."

After Abacha’s coup, tensions worsened. The regime exploited divisions within the movement. In May 1994, four Ogoni leaders were murdered, and the government accused Saro-Wiwa and eight others of involvement. Despite global outrage and international awards recognising his activism, the “Ogoni 9” were sentenced to death and hanged on November 10, 1995.

Worldwide condemnation

The executions provoked worldwide condemnation, leading to Nigeria’s suspension from the Commonwealth of Nations for more than three years.

Some witnesses later alleged they were bribed by the government or that Shell had promised them jobs. The company’s precise role has never been fully clarified. In 2009, Shell paid $15.5 million (about €13 million today) to the families of the Ogoni 9, calling it a "humanitarian gesture" rather than an admission of guilt.

Priscilla Airohi-Alikor, an economist at the Centre for the Study of the Economics of Africa, says progress on cleaning up oil pollution in the Niger Delta has been painfully slow. One key achievement of the MOSOP movement, she notes, is that "Shell has not drilled oil in Ogoniland since 1993."

Still, leaks from old facilities continue to poison the environment.

After Abacha’s dictatorship ended, Nigeria created the Niger Delta Development Commission (NDDC). In 2016, then-President Muhammadu Buhari launched a multibillion-dollar cleanup effort based on UN recommendations.

Compensate farmers

Shell’s accountability remains central. In 2021, following years of litigation, the company was ordered to compensate farmers affected by oil spills in the Niger Delta.

"In most cases, they've actually settled with a lot of these communities," says Airohi-Alikor.

"But it's on the admission that they shouldn't be held liable for what these communities are suffering. The company has also evaded a cleanup of the community."

According to Airohi-Alikor, Shell argues that most pollution results from sabotage.

In June, a British court ruled that Shell can indeed be held liable for environmental damage in the Niger Delta — though it remains unclear whether this will lead to binding verdicts.

Thirty years after the execution of the Ogoni 9, Nigeria’s government posthumously pardoned Ken Saro-Wiwa and his eight colleagues, awarding them national honours. The four Ogoni leaders murdered in 1994 were also recognised.

For Nnimmo Bassey, the gesture rings hollow. "That is not enough. You do not pardon a man who did not commit an offence," he said.

Shifting to deep-sea drilling

He argues that accepting such a pardon implies guilt. Bassey is also angered that Nigeria continues to pursue new oil projects in the Niger Delta while the old pollution remains unresolved.

Shell, he warns, is now shifting to deep-sea drilling — beyond national jurisdictions. In his view, it’s time to move beyond fossil fuels altogether.

Oil, petroleum products, and gas account for between 85 per cent and 92 per cent of Nigeria’s export revenue. Yet the country is increasingly battered by floods and heatwaves linked to climate change — and needs resources to cope.

To Airohi-Alikor, Saro-Wiwa’s decades-old warning not to depend on oil now seems prophetic. "If the country does not take action in due course, oil revenues would go into cleaning up these communities. If we account for the environmental cost of gas flaring or oil spillage, you find that the nation is at a loss."

Top Stories Today